Compared to West Africa, whose history is far more and far longer integrated into the Atlantic political and cultural economy, East Africa is rural and sparsely populated. This region stretches from Kenya and Uganda in the north to Tanzania or northern Mozambique in the south. Perhaps the exception to the rule of the region’s historically low population density is the Interlacustrine peoples of Rwanda and Burundi. The region is united not just by the demographic dominance of Bantu-speakers but also by the spread, in recent centuries, of Kiswahili specifically, a Bantu language originating on the Indian Ocean coast among the monsoon-borne millennial maritime trade with the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian sub-continent, and China. In terms of their material culture, the Swahili Coast is perhaps most famous for its stone architecture, the pastoralists of the interior for their magnificent beaded leatherwork and jewelry, and the farming peoples, such as the Makonde and the Nyamwezi, for a tradition of wood-sculpting, sacred masquerades, and ancestor-veneration that share a common legacy with the peoples of the Central and West African tropical forests.

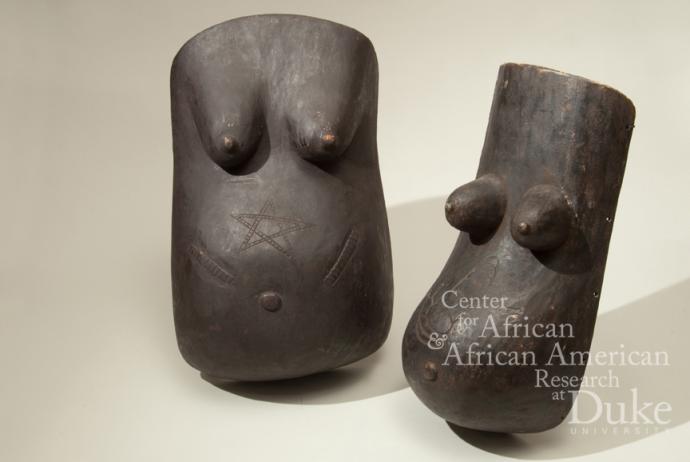

Southern Africa includes the nation-states of Mozambique, Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho, and Swaziland. This is a largely Bantu-speaking region, although the local language and culture have also been influenced by the longer-resident Khoisan-speakers and the more recently arrived Dutch, English, and south Asian settlers. The northern reaches of southern Africa—including Mozambique, Zambia, Angola, and Zimbabwe–include a number of forest and savannah peoples famous for their masking traditions, such as the Bemba, the Lunda, and the Chewa and the Yao peoples. Matriliny is common in a belt of societies stretching from Angola in the east and into Zambia. That is, inheritance and family membership are traced chiefly through the mother’s and the mother’s mother’s line. The Shona people of what is now Zimbabwe are famous for their stone masonry and carving, some of which is associated with rites for ancestral spirits. Shona spirit possession priests were actively involved in articulating resistance against the white-minority government in what was then Rhodesia.

Farther south is a climate of savannah and Mediterranean-like conditions that host a rich cattle complex, in which cows have historically been the focus of economic production and a major medium of social relations. Here, bridewealth, bloodwealth, and other indemnities were historically and still often are paid in cattle. Thus, membership in the patrilineage, the predominant kinship form of this region, correlates with ownership and access to cattle, and the products of the cow are employed in communications with the ancestors. Here, as in the East African cattle complex of Kenya and Tanzania, bovine leather and imported European seed beads are combined in ceremonial attire and especially in the gorgeous outfits worn during female rites of passage.

Christianity is a centuries-old presence in southern Africa, brought in various denominational forms by Dutch Calvinists, British Anglicans, and African-American Methodists. At the beginning of the 20th century, independent African churches emerged to articulate indigenous Africans’ unique experience of the Christian god, their own interpretation of biblical social ethics, and their rejection of white racial discrimination in the European-dominated churches. Most southern Africans are Christians, but the majority also consults with diviners known widely as sangoma and herbalists known as ingoma, both from the Zulu terms. Ingoma provide herbal solutions to physical problems, but ingoma and sangoma overlap in the aim heal and to prevent misfortune through the divinatory casting of bones, through protection against witchcraft, and through the maintenance of harmonious relations between their clients and the ancestors of those clients.