The most Westernized of African-diaspora peoples, African Americans nurse an old love-hate relationship with Africa. During much of the history of the United States and of its colonial antecedents, African ancestry was equivalent to a mark of enslavement and long remained a bar to full citizenship rights. Many African Americans therefore favored and favor European physical features and seek to distance themselves culturally from Africa. On the other hand, a long thread of ethno-political pan-Africanism stretches back to the naming of the 18th-century African Methodist Episcopal Church, the African emigrationist movement and the founding of Liberia in the early 19th century, and the massive Garveyite movement of the early 20th century.

Nonetheless, scholars such as W.E.B. DuBois, Melville J. Herskovits, and Lorenzo D. Turner perceived the tacit cultural influence of Africa in African-American music and dance, dress, language, charismatic Christianity, and forms of magic known as “Hoodoo” and “Voodoo.” Beginning in 1930, African-American anthropologist and dancer Katherine Dunham developed a hybrid performance style based upon Caribbean, African, and African-American music and dance, and, beginning in the 1940s, Trinidadian-American anthropologist and dancer Pearl Primus introduced her own African-inspired dance style to the night clubs and proscenium stages of New York City. However, self-consciously African-centered cultural nationalism did not take root on a large scale only after World War II, as a cascade of African and Caribbean nation-states achieved political independence and, amid frustration with the progress of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, the more radical Black Power Movement arose.

Among the products of this era was Walter Serge King, who danced in Dunham’s company and, during a visit to Haiti, became interested in African-inspired religion. In 1959, King traveled with Cuban-American friend Christopher Oliana to the Cuban province of Matanzas, where King was initiated as a priest of the Afro Cuban oricha of wisdom and purity Obatalá and Oliana as a priest of the oricha of the volcano Agallú. Thereafter, King renamed his religion “Orisha-Voodoo” and endeavored to expunge its Roman Catholic elements. He then founded a series of temples devoted to Orisha-Voodoo in New York City, then finally moving his community of followers to Sheldon, South Carolina, where the established Oyotunji African Village. There, his followers built dozens of thatch- and corrugated-iron-roofed buildings with elaborately carved veranda posts, in imitation of Nigerian Yoruba palaces. As the town’s ruler, King took the name Ofuntola Oseijieman Adelabu Adefunmi I. In 1981, Adefunmi I was crowned a town monarch, or ǫba, by the monarch of the sacred Yoruba city of Ile-Ifę. After his death in 2005, he was succeeded by his son Adejuyigbe Adefunmi (a.k.a. Adefunmi II).

Over time, increasing numbers of African Americans have undergone initiation in Cuban-American Santería/Ocha, traveled to Nigeria for initiation in Yoruba ęsin ibilę, or been initiated by Nigerian orişa priests in the United States, Oyotunji African Village remains the capital of a distinctly African-American tradition of orisha-worship. It is perhaps the only and is almost certainly the oldest fixed and publicly accessible temple of orisha-worship in the United States, where most worship is conducted in private homes or rental venues that serve only temporarily as places of collective, public worship. Among the other distinctions of Oyotunji are its formal practice of polygyny and its commitment to Black racial nationalism. No other major tradition of orisha-worship in the Americas or Africa excludes people of other races from initiation, and no other such tradition in the Americas formally endorses plural marriage. Oyotunji’s leaders regard Yoruba religion as the core of Black people’s shared ancestral legacy, and they regard white devotees as interlopers, ready to take control over the religion at the first opportunity.

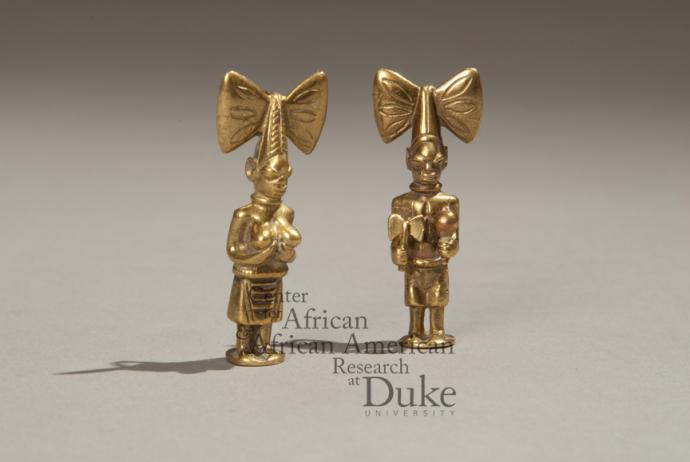

Another influential leader of African-American orisha-worship is John Mason, the leader of the Brooklyn-based Yoruba Theological Archministry and author of nearly a dozen historical and theological texts, a song book that translates previously untranslated ritual songs (Orin Orişa: Songs for Selected Heads [1997]), and, along with John Henry Drewal, a book on Yoruba-Atlantic beadwork called Beads, Body, and Soul: Art and Light in the Yoruba Universe (1997). Mason’s Archministry seems to have been an important distribution center for the fine silver, iron, and brass miniature statuary and lapel pins made by African-American sculptor Ogundipę Fayǫmi during the 1980s and ‘90s.