Although the region is also home to many Muslims, Hinduism is the dominant religion of South Asia, and Buddhism the dominant religion of Tibet, China, Japan, Korea, and continental Southeast Asia. Hinduism is an internally heterogeneous religion that has come to be considered a single tradition only since the era of European colonialism. Among its centripetal values are caste, reincarnation, the continuity of duty and guilt across multiple lifespans, the renunciation of maya, and the belief that the supreme being manifests itself in innumerable personalities or gods, such as Brahma (the Lord of Creation), Vishnu (the Lord of Preservation), and Shiva (the Lord of Destruction). Together, they manifest the continual and inevitable cycle of existence.

For Hindus, the ultimate aim of the soul is to transcend the illusion that the material world is important or real (maya) and to escape the cycle of reincarnation and become one with the universe—that is, to achieve nirvana. The bodily practices associated with such transcendence, such as cross-legged meditation, are quite different from the practices associated with Afro-Atlantic religions, as both of these traditions of bodily praxis differ from those of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

The most important shared scriptures of these ideas are the texts known as the Vedas and the epic poem known as the Mahabharata, texts passed down and then written by the western and central Asian invaders of the Indian subcontinent. They are thousands of years old.

Buddhism emerged from the same family of religions that came to be known as Hinduism and shares many of the same principles—such as reincarnation, the continuity of duty and guilt across multiple lifespans, and the renunciation of maya but not the practice of caste and not necessary the belief in gods. The prototypical hero of Buddhism is a historical figure named Siddhartha Gautama, a prince who, in the 6th century BCE, renounced both princely luxury and the extremes of self-denial modeled by the many other clerics of the Vedic tradition. He also renounced caste. Thus, he exemplifies the adoption of a moderate path toward nirvana.

Buddhist traditions entail the veneration of the original Buddha and of the subsequent teachers who have achieved nirvana, as well as those who have postponed their transcendence in order to help others advance toward this goal (bodhisattvas). Yet, only in some Buddhist traditions are these figures treated as super-human gods. In others, they are merely regarded as virtuous human beings, much as Muslims regard Mohammed.

Wherever they are practiced in Asia, Europe and the Americas, today’s Hinduism and Buddhism reflect not only their millennial history among the Aryan invaders of south Asia but also the diverse local traditions that preceded their arrival, such as Taoism in China and Shinto in Japan.

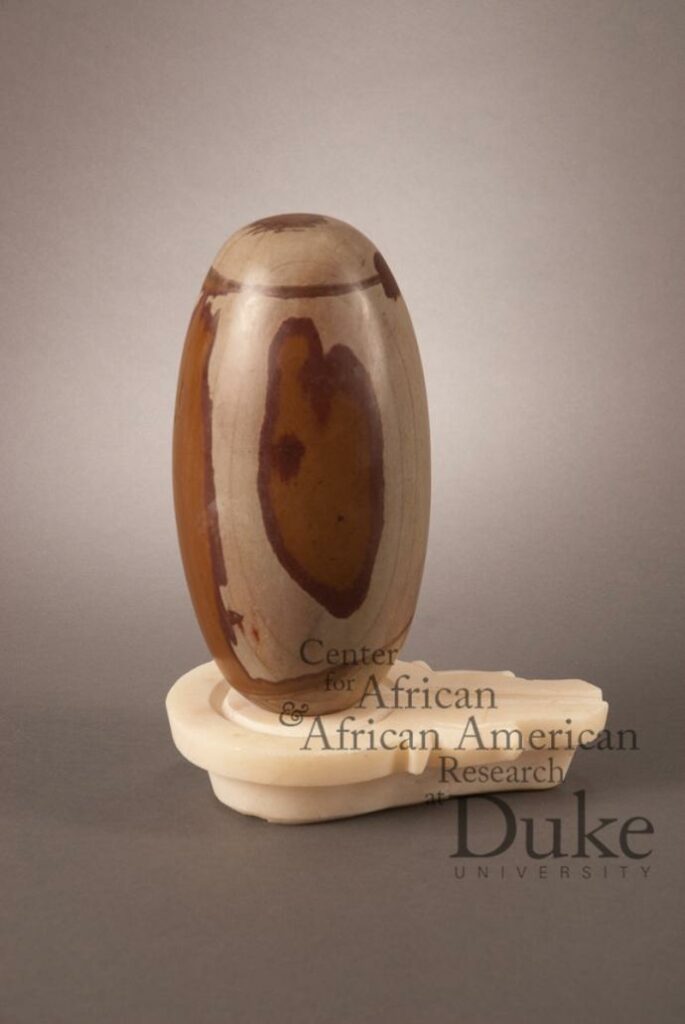

Both Hinduism and Buddhism have produced elaborate traditions of anthropomorphic and abstract stone-carving, ceramic statuary, and architecture. In the CAAAR Collection, both Hindu and Buddhist sacred forms are presented as contrast cases illustrating what is distinctive about Afro-Atlantic iconographies and sacred bodily postures. Yet Chinese statuary is presented also because 19th-century Cuban santeros, or oricha-worshipers, adopted sacred personae, iconography, and magical practices from the hybrid Taoism/Buddhism of Chinese immigrants to Cuba, incorporating them into Santería/Ocha.