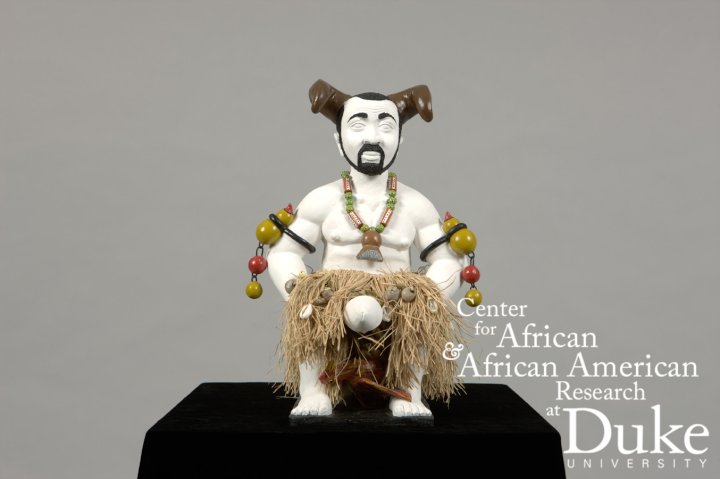

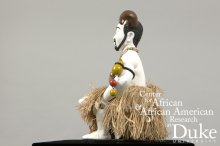

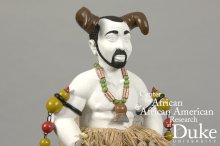

Euloge Sénoumantin Ahanhanzo Glèlè

10.08" x 9.89" x 14.5"

256.11 mm x 251.20 mm x 368.3 mm

Legba is a good of phallic fertility, doorways and communication between humans and gods. He is comparable to and probably historically related to the Yorùbá god Èṣù. The name “Legba” is probably etymologically related to Èṣù’s òríkì (or attributive poetry name) “Elégbára.” Cognates of the Fon name Legba with names cognate to his are found in the Jeje nation of Brazilian Candomblé (Leba), the Rada nation of Haitian Vodou (Papa Legba), and New Orleans Voodoo and Hoodoo (Papa Legba).

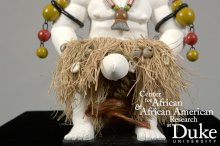

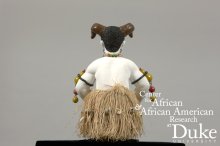

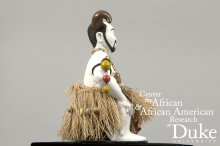

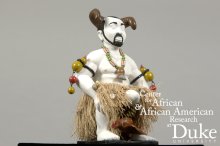

Although the name of this piece, the curved horns on its head and its the large phallus are clearly legibile references to the Fon god Legba, the figurative representation of the god in this work of art, its white skin color and the color scheme of the ceramic “medicine calabashes” distinguish it sharply from the normally cowry- and wood adorned lateritic mounds that embody Legba at the entryways of Fon traditionalist residential compounds. The white skin color of this figure muddies the Western premise that hyper-sexuality defines blackness in contrast to whiteness. And a viewer sensitive to Afro-Atlantic anthropology and cosmology will read Legba’s visibly large and erect penis not as lewd and dangerous disruption to dignified public life but as the paradigm of the mutually fecundating encounter between not only genders but also cultures, races, generations, the living and the dead, humans and gods. And what are we to make of the fact that the empowering and protective ceramic “medicine calabashes” worn be this white Legba resemble nothing more that the pimento-stuffed martini olives of mid-century modern America’s key parties, and that they hardly resemble at all the medicine calabashes worn by the gods and priests of the Fon and the Yorùbá. Glèlè would most certainly know at least the latter fact. And he might have noticed the former fact in the post-WWII imagery of US American movies and films about the post-War French business elites who imitated US American drinking habits. And, of course, neither he nor other contemporary African studio artists are the first African artists to appropriate Western aesthetic forms. The great extent of that appropriation is a major difference between, on the one hand, Yoruba art and, on the other, Fon and Kongo royal art.

This piece intervenes with literalism and irony, hope and despair in a genealogy mutual appropriation between African and European artists, in which African sacred art, usually created by artists whose identities have been absorbed into tribal collectives as imagined by European art dealers and collectives, has served as touchstones of 18th- and 19th-century bourgeois Europeans’ and Euro-Americans’ efforts to prove themselves equal–by virtue of their white skin, their taste for highly figurative art and their ostentibly restrained sexuality–superior to Africans and therefore equal to European royals, aristocrats and popes. In the early 20th century, similar African sacred art became a major touchstone of efforts by the Cubists, the Fauvists, the Surrealistes and a range of other European intellectuals to transcend the forms of social hierarchy, emotional repression and naturalistic aesthetic forms that had survived the Enlightenment’s rebellion against crown and miter. After each of the European-centered world wars of the 20th century, such African sacred art became additionally emblematic of European progressives’ rejection of Enlightenment-inspired racism and high-tech destruction of life and of the natural environment.

In this genealogy of racialized aesthetic and ethical debate, the studio-trained African artists face multiple dilemmas. For example, how does one exploit one European generation’s positive stereotypes about Africans while avoiding the implications of a prior European generation’s attachment of negative values to the same stereotypes? And, in the tradition of other studio artists from colonized or marginalized nations trying to generate a creditably unique contribution to the studio art tradition of the European or North American metropolis, how does the nationally marginal artist turn the stereotyped and denigrated folklore of his or her unassimilated compatriots into a thing of dignity.

With his naturalistic, European color-coded, grass-skirt-wearing, horned and enormously endowed royal-looking “Legba,” Glèlè has made a provocative intervention, indeed.